This article has been written by guest post blogger, Bruce Greig, who offers some fantastic ways you can teach your students to learn rapidly!

Learning by rote has, to put it mildly, somewhat gone out of fashion since the days of rows of Victorian schoolchildren reciting their times tables in unison.

But there is no getting away from the fact that learning involves remembering information, and some types of information just have to be learnt by heart. The obvious examples are multiplication tables and foreign language vocabulary.

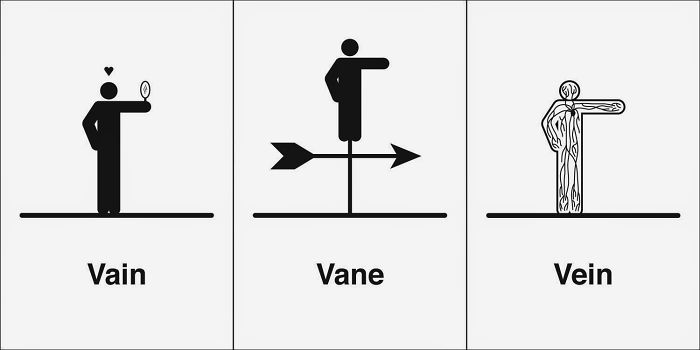

There are two techniques used by memory gurus which are almost never taught in schools: visualisation and spaced repetition. Visualisation might be touched on sometimes, like these kinds of aide-memoires:

Learning by rote has, to put it mildly, somewhat gone out of fashion since the days of rows of Victorian schoolchildren reciting their times tables in unison.

But there is no getting away from the fact that learning involves remembering information, and some types of information just have to be learnt by heart. The obvious examples are multiplication tables and foreign language vocabulary.

There are two techniques used by memory gurus which are almost never taught in schools: visualisation and spaced repetition. Visualisation might be touched on sometimes, like these kinds of aide-memoires:

But schools don’t teach visualisation in the way that memory gurus use it. Few people realise how effective visualisation can be. Take the parlour game trick of memorising the order of a randomly shuffled pack of cards. Magician shuffles the cards, looks at them one at a time, then goes through the pack again, correctly predicting each card as it comes up. Impressive as it looks, anyone can do this with about an hour’s practice.

The technique is to imagine walking along a familiar route and at key places you mentally position some outrageous image representing each playing card. Young man ripping out his own heart while hanging from lamppost at the corner of your street: Jack of Hearts. Five workmen digging furiously to pull down the lamp post: five of spades. And so on. Try it with twenty cards, you’ll find it surprisingly easy.

Memorising a pack of cards is, of course, completely useless. But this trick illustrates how effective visualisation can be: imagining a powerful, even outrageous, image makes recall very easy.

Learners can do the same thing with foreign vocab and multiplication tables. The crucial step is to make the effort think up an image the very first time you are presented with the word to be remembered. Do this the first time, for every word, even if it takes thirty seconds or a minute to do. It is effortful, much more so than just reading or hearing the word and hoping to remember it. But that effort will be repaid many times over as the recall becomes easier and easier based on the image you have for that word.

Which brings us onto the second technique beloved of memory gurus but almost never found in the classroom: spaced repetition. This was originally a flashcard technique. You start with one pile of flashcards. As you review each card you judge how easy you found it to recall the answer. Easy cards you upgrade into a new pile, hard ones stay in the same pile. The next day, you only review your “hard” pile, ignoring the easy pile. You revisit the easy ones in, say, two days and again promote those you still find easy into a new pile, downgrade hard ones back to pile one, and keep the rest where they are.

Over time, you build up to having a pile of cards you need to review every day, another pile you only look at once a week, and so on, up to a pile which you might review once a year.

The fascinating insight of this technique is that you eventually get to the point where you review each card just around the time you are starting to forget it. You don’t waste any time reviewing cards that you still remember well. That is why it is so efficient: you only review the cards that you need to, you don’t spend any time on other cards.

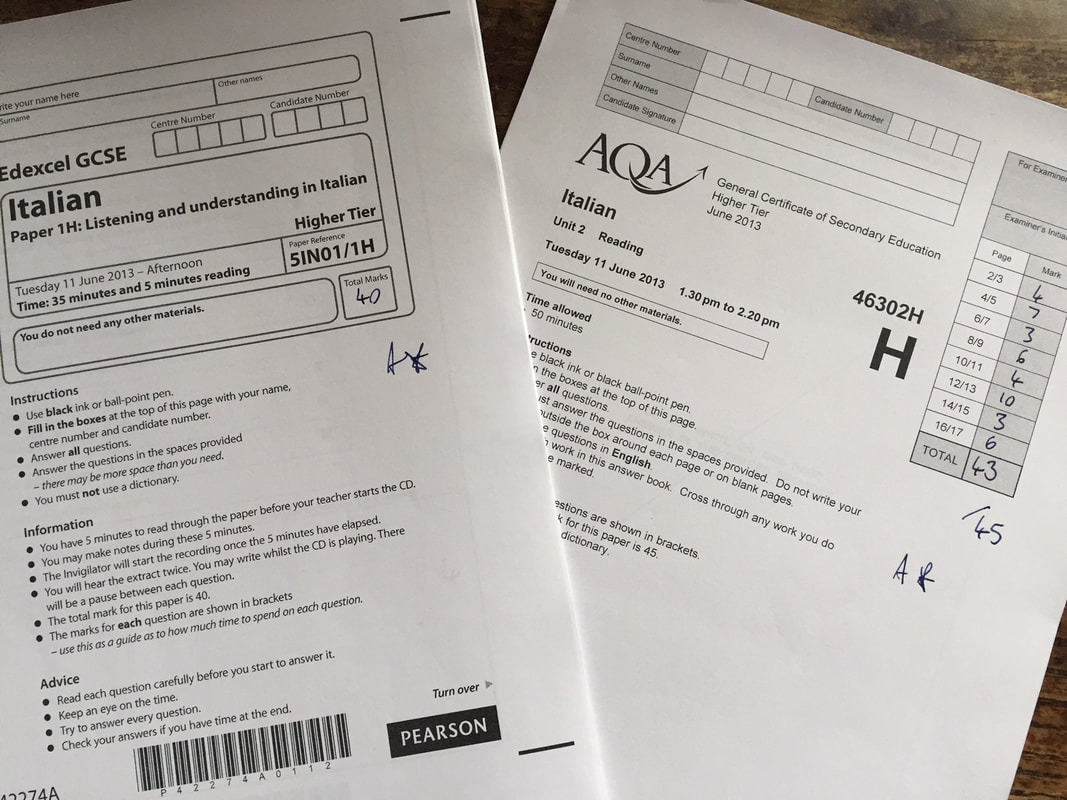

I used this technique to learn good tourist-level Italian. Curious to rate my own ability I did an Italian GCSE past paper. I completed the paper to A* level, and found the paper far less intimidating that my French and Spanish GCSEs from years ago.

The technique is to imagine walking along a familiar route and at key places you mentally position some outrageous image representing each playing card. Young man ripping out his own heart while hanging from lamppost at the corner of your street: Jack of Hearts. Five workmen digging furiously to pull down the lamp post: five of spades. And so on. Try it with twenty cards, you’ll find it surprisingly easy.

Memorising a pack of cards is, of course, completely useless. But this trick illustrates how effective visualisation can be: imagining a powerful, even outrageous, image makes recall very easy.

Learners can do the same thing with foreign vocab and multiplication tables. The crucial step is to make the effort think up an image the very first time you are presented with the word to be remembered. Do this the first time, for every word, even if it takes thirty seconds or a minute to do. It is effortful, much more so than just reading or hearing the word and hoping to remember it. But that effort will be repaid many times over as the recall becomes easier and easier based on the image you have for that word.

Which brings us onto the second technique beloved of memory gurus but almost never found in the classroom: spaced repetition. This was originally a flashcard technique. You start with one pile of flashcards. As you review each card you judge how easy you found it to recall the answer. Easy cards you upgrade into a new pile, hard ones stay in the same pile. The next day, you only review your “hard” pile, ignoring the easy pile. You revisit the easy ones in, say, two days and again promote those you still find easy into a new pile, downgrade hard ones back to pile one, and keep the rest where they are.

Over time, you build up to having a pile of cards you need to review every day, another pile you only look at once a week, and so on, up to a pile which you might review once a year.

The fascinating insight of this technique is that you eventually get to the point where you review each card just around the time you are starting to forget it. You don’t waste any time reviewing cards that you still remember well. That is why it is so efficient: you only review the cards that you need to, you don’t spend any time on other cards.

I used this technique to learn good tourist-level Italian. Curious to rate my own ability I did an Italian GCSE past paper. I completed the paper to A* level, and found the paper far less intimidating that my French and Spanish GCSEs from years ago.

This after around a dozen hours of hours of study, rather than the many hundreds of hours of study I must have spent doing French and Spanish at school twenty-five years ago.

Spaced repetition is extremely effective, but there is a good reason that it isn’t commonly used in classrooms: it is completely impossible for a teacher to administer. The teacher cannot keep track of how well each child remembers every word in their foreign vocab list; or how well each child remembers every multiplication fact.

The only practical way to use this technique in a classroom is for every child to manage their own “piles” of cards. Either with real cards, and real boxes to place them in or (more practical) an app like Anki which recreates this exact technique on a screen. Some language learning apps like Memrise and Duolingo do use elements of spaced repetition, but in my experience a simple flashcard system, using spaced repetition (as Anki does) is all you need.

I’ve encouraged my daughter to use these techniques for her school Spanish, and it works very well. Are you a teacher who has used these techniques in your classroom? We’d love to hear from you in the comments below.

(About the author: Bruce Greig is an entrepreneur and school governor. He has a psychology degree from Oxford University. He served as CoG through two Ofsted inspections and four headteachers. He runs SchoolStaffSurveys.com in his spare time, after discovering how enlightening an anonymous staff survey can be and decided to make it easy for every school to run them.)

Spaced repetition is extremely effective, but there is a good reason that it isn’t commonly used in classrooms: it is completely impossible for a teacher to administer. The teacher cannot keep track of how well each child remembers every word in their foreign vocab list; or how well each child remembers every multiplication fact.

The only practical way to use this technique in a classroom is for every child to manage their own “piles” of cards. Either with real cards, and real boxes to place them in or (more practical) an app like Anki which recreates this exact technique on a screen. Some language learning apps like Memrise and Duolingo do use elements of spaced repetition, but in my experience a simple flashcard system, using spaced repetition (as Anki does) is all you need.

I’ve encouraged my daughter to use these techniques for her school Spanish, and it works very well. Are you a teacher who has used these techniques in your classroom? We’d love to hear from you in the comments below.

(About the author: Bruce Greig is an entrepreneur and school governor. He has a psychology degree from Oxford University. He served as CoG through two Ofsted inspections and four headteachers. He runs SchoolStaffSurveys.com in his spare time, after discovering how enlightening an anonymous staff survey can be and decided to make it easy for every school to run them.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed